Joe Turner’s Come and Gone by August Wilson. Directed by Lili-Anne Brown. Staged by the Huntington Theatre Company at 264 Huntington Avenue, Boston, through November 27.

By Robert Israel

The Huntington Theatre Company’s reprisal of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone hits most of the right notes, despite some missteps and miscasting bumps along the way. The staging faithfully captures playwright August Wilson’s searing poetic vision, which means you should attend this production. This is a solid, stirring dramatic experience that captures the plight of restless characters whose lives pivot on the fringes of elusive self-discoveries.

Backward glancing: 36 years ago I reviewed the first production of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone at HTC. Much indeed has “come and gone.” Wilson died in 2005, completing 10 scripts that depicted African American life for each decade of the 20th century (his acclaimed “American Century Cycle”). He left behind a trove of indelible memories, like the time at Ann’s Cafeteria on Huntington Ave. (now Ginger Express), he let me witness him arguing with one of his characters. “That’s the only way I know what they want me to write,” he explained to me. Gone, too, is director and former Yale Drama School dean Lloyd Richards, who died in 2006, and who schooled Wilson in the art of stagecraft. And mourned since 1991 is actor Ed Hall, who created the role of Bynum Walker; Hall and I were neighbors in Providence when he was a Trinity Rep actor and I wrote for the Providence Phoenix — you guessed it — a newspaper gone since 2014.

The drama is set in the playwright’s hometown of Pittsburgh in 1911, and Wilson, in his published text, describes this particular era as one of constant upheaval. He tells us his characters have traveled from the scorched earth of the South as “newly freed African slaves…cut off from memory…[and] arrive dazed and stunned, their heart kicking in their chest with a song worth singing.” Wilson’s figures, haunted by the past and wary of future, are in search of kindred spirits who can help them find ways to make their uprooted existences meaningful. Director Lili-Anne Brown is challenged to do justice to the theatrical power of a script that probes, at its core, how these embattled characters find (or ignore) their songs as, in Wilson’s phrase, “foreigners in a strange land.”

As the curtain rises, we meet boardinghouse owners Seth Holly (Maurice Emmanuel Parent) and his wife Bertha (Shannon Lamb). They run a “respectable” establishment — this is no barrel house. The men, women, and children who drift in and out of this space transform it into a way station filled with lost souls who are at odds with each other. Still, they share several things in common. Each is searching for an anchor, a place of belonging; each must eke out a living; each is yearning for love – from each other — and some sort of respite from an indifferent God.

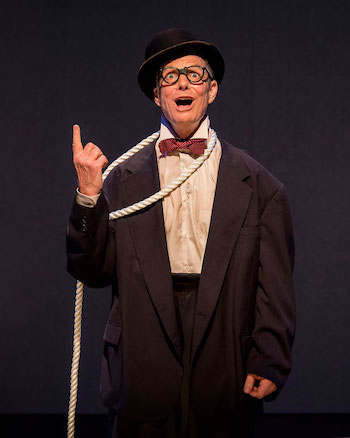

And so, like the “rootworker” Bynum Walker (Robert Cornelius), they surrender to their various superstitions: burning incense, humming incantations, scratching the hardscrabble earth for herbs to make potions that “bind” people together. Or the connections are made by itinerant business men, like Rutherford Selig (Lewis D. Wheeler), who travels from town to town, pots and pans held together by a hank of rope on his back. He also helps folks find missing loved ones (always for a small fee). The play is made up of surprisingly transactional relationships — some promise to provide services, others are desperately in need of those services.

There is the sexual tension, of course Jeremy Furlow (Steward Evan Smith) is on the perpetual make. He has a guitar on his back and with it woos women aplenty who can’t resist his charms. Wilson does not develop his female characters with much depth here, serving up gender stereotypes. The wonderful actress Shannon Lamb does wonders with the role of Bertha Holly, ladling on an adroit feistiness.

The production falters with the appearance of the youngest members of the cast (Gray Flaherty and Eli Lapaix), who play Zonia Loomis and Reuben Mercer. They fail to convey the spirit of the next generation, one filled with hope. During the performance I attended the pair were unable to project their lines effectively and, sadly, lacked stage presence.

Kudos should go to scenic designer Arnel Sancianco, who has created a set that is airy and open, enabling fluidity of movement. Costume designer Samantha C. Jones excels, as does Jason Lynch’s lighting: at times bright with the promise of a better day and, alternatively, bathed in purple to suggest darker portents.

The production also ushers in a newly designed HTC auditorium with more comfortable seating and a newly dedicated August Wilson Lobby. Politically, this staging is a welcome event in these backsliding times — we sorely need Wilson’s poetic voice. Joe Turner’s Come and Gone challenges us to confront difficult memories and to face our collective responsibility. Have we lost our way as a community? Can we regain our sense of purpose and direction? Wilson’s characters are not afraid of baring their souls, an invitation for us to do the same.

**

A version of this review appeared in the October 25th edition of The Arts Fuse magazine (Boston).