And So We Walked: An Artist’s Journey Along the Trail of Tears, a one-woman play written and performed by DeLanna Studi. Directed by Corey Madden. Presented by Arts Emerson at the Paramount Center, Orchard Stage, 559 Washington St., Boston, MA, through April 30.

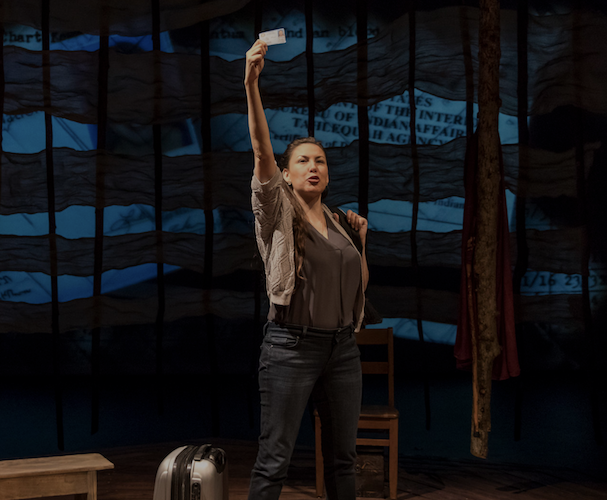

DeLanna Studi in And So We Walked. Photo: Octopus Theatricals

By Robert Israel

Not long after opening curtain, DeLanna Studi holds an identification card aloft. In her at times compelling but most often tedious two-hour one-woman show, we are told that this card identifies her as a full-fledged member of the Cherokee nation. Born in Oklahoma to mixed parentage — like our own Sen. Elizabeth Warren — she clarifies that claim: she’s a “half-breed,” an appellation I assumed to be derogatory. But not necessarily. And So We Walked is about the performer finding her roots and that quest is often meandering. That, as well as all the myriad details that pile up during her search, end up weighing the show down, especially when she is probed by others she meets regarding her understanding of her Cherokee/Caucasian ancestry.

Studi takes us along with her father (she assumes all personas) as she confronts uncomfortable questions about her ancestry. Father and daughter are on a trek along the Trail of Tears. This is the traumatic path that Native Americans took in 1830 – a forced march that left over 4,000 dead. I attended this play only a few weeks after Passover, and I could not help but draw a comparison between that tumultuous journey and the quest my ancestors took through the Sinai desert millennia ago. This similar expulsion lasted, according to the Hebrew Bible, 40 years to complete. It’s an important story to remember, because we are not out of wildness yet. We are told in a prayer at the Seder table, “not only one enemy has risen up to destroy us, but in every generation they rise up to destroy us.” The growth in contemporary outbursts of ethnic and religious hatred in the United States are evidence that these enemies are increasing around us. But Studi evokes no Biblical resonance in her vision of her ancestor’s struggles. She does not dramatize exile as a powerful theatrical metaphor — her show is stripped bare of poetic symbolism.

Instead of providing full-bodies drama, Studi retells her journey through an accumulation of details … and more details. To the point that And So We Walked comes off as a tour through the items in a catalogue. The performer’s tone is flat and usually prosaic; there is no attempt to evoke the spiritual importance — and agonies — of the Native American experience. When she does share an emotional outburst – her hatred of President Andrew Jackson, for instance – we see the fire in her eye. But that’s a rare occurrence.

The giveaway is when she turns to us, standing center stage near the close of the show, and exclaims:“I haven’t had an epiphany!” She’s been waiting on that thunderclap, that blast that will stir her soul. Somehow it has escaped her.

A gifted thespian, Studi peppers And So We Walked with moments of physical vigor as she nimbly moves about the stage. She uses only a handful of props – a scarf, suitcases, a backpack, a cell phone. Norman Coates’ lighting helps to bring the visuals of her journey to the fore, most notably when Studi shares her perception of fireflies. We see, magically projected against the back wall of the stage, small blots of light rising skyward, destined to mingle with the stars in the night sky. If only the audience were treated to more experiences like this. Dangling out of reach is a moment when Studi realizes that she and her people have an indispensable place on this planet, that she understands the meaning of her ancestors’ hardships. All the alienated pieces stitched together. But that never happens.

Studi’s play comes at a time when Americans are seeing more work by Native Americans, such as the scripts of playwright Larissa Fasthorse, who has written The Thanksgiving Play, a revealing look at the dark side of our national holiday. (Now slated for a Broadway production.) Studi is seizing the day: it is a time of national introspection as we probe the country’s problematic past regarding issues of ancestry, identity, and race. But when creating compelling drama, listing injustices and inequalities is not enough. In this piece Studi needs to pull the audience in, forcing them to see how their personal stories interact with collective histories. Which means commanding, perhaps even expanding, theater’s storytelling potential. And So We Walked does not do that. It is a missed opportunity.

**

A previous version of this review appeared in The Arts Fuse (Boston) on April 28, 2023.