Peirson House, Richmond, MA (Library of Congress photo)

Washington Irving described the fictional town of Sleepy Hollow as a place that “continues under the sway of some witching power that holds a spell over the minds of the good people, causing them to walk in a continual reverie. They are given to all kinds of marvelous beliefs, are subject to trances and visions, and frequently see strange sights, and hear music and voices in the air.” Irving could have been waxing rhapsodic about the bucolic Berkshire County, Mass., in the decades before it became overrun by wealthy Bostonians and New Yorkers who transformed its quaint, somnambulistic hamlets into tony second-home enclaves with all the trappings.

I met Margaret Mace Kingman just before the real estate grubbing took place. She often seemed like she stepped out of Washington Irving’s tale. She had an other-worldliness about her. She moved about Peirson Place, a pre-Colonial estate in Richmond, Mass., her silver hair tied in a tight bun, and she favored wearing throw-back laced aprons, Amish-style, with rough hewn woolen sweaters and clogs. A former university science professor who had previously served as a CIA spy overseas and in Washington, D.C, she had returned to her birthplace to become an innkeeper.

It was the late 1970s. I had been scouting affordable places to stay so I could attend Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts in Lenox, five miles away. Margaret offered me a room in the barn in exchange for chores around the property. She let me borrow a bike, and I pedaled along roads with views of the Taconic Range. During summer mornings, I’d swim in Richmond Pond in the shadow of Lenox Mountain, or drive along Swamp Road past farmland populated with barns, abundant crops, and livestock. In the nearby town of Hancock, which abutted her land, I found grassy lanes once trod upon by Shakers who built the circular barn (still used today by caretakers at the Hancock Shaker Village). A sense of timelessness pervaded the paths where creeks gurgle musically before vanishing underbrush to join larger streams and rivers.

I was working on my graduate school thesis on Herman Melville – he once called Berkshire County home on a farm called Arrowhead in nearby Pittsfield. During pristine summer days he wrote that he experienced the “all” feeling — a brief respite from the “carking cares of life” and the pressures of raising his family as an author of unpopular books. Margaret and I often sat on the screened porch of Peirson Place talking about Melville and Hawthorne (who summered in Lenox), or she’d share stories about Richmond summer residents such as sculptor Alexander “Sandy” Calder who cobbled together mobiles in a nearby barn, or futurist Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller who erected his geodesic domes in an open field, or “Fanfare for the Common Man” composer Aaron Copland, and others.

But she took more delight talking about her wildlife friends. She had assigned snakes first names and I watched as they slithered about and lay, half-coiled, on the moist flagstones she had placed for them near the Hoyas and wildflowers.

During one of our many walks about the property, she pointed out the paths she created to accommodate the blind students who visited from the Perkins School in Watertown, Mass. She and a landscaper created what she called a “smell and tell trail” so blind students could experience the area’s unique fauna and flora.

“The suggestion came from a blind student,” Margaret said. “We called it a ‘smell and tell trail’ we placed posts here and there with descriptions written in Braille. One of the students said, ‘What building is that?’ I replied, ‘There is no building there,’ but he insisted, saying, ‘Yes, there is a building there.’ And he described how many feet away it was. I said, ‘But there isn’t any building. Let’s walk down.’ True enough, my neighbors had built a new garage there I didn’t know about, and, of course, he could get the echo. And from the echo he could tell me how big it was and how far away it was.”

That led her to discuss the bats that lived in her barn and how they use ecolocation to find each other and places where they feed. Just then I saw as they streamed past us, leaving inky streaks against the pale sky.

“We have a large population of bats,” she continued. “You notice I have a bat house up here and another one there. They feed off those pesky mosquitoes and gnats and such. It looks like they touch the surface of the pond, but they only skim it. One time I had the Richmond Boy Scouts over, and I teamed them off with the blind scouts from Perkins so they could work on a merit badge about bats.”

I spent a few nights camping behind the pond. Margaret told me the trail had once been used by Native Americans. I never followed it, but learned it led to Chatham, New York, and then meandered along until it reached the banks of the Hudson River, 14 miles away.

One morning I mentioned I had been out to dinner in West Stockbridge, around six miles away. I had returned late. There was no moon, only starlight, and the place was pitch-dark. I had forgotten my flashlight. I entered the woods with trepidation, waiting until my eyes adjusted to the darkness. To my surprise, the path to my campsite was lit with scattered bits of phosphorescence as if placed there on purpose. I found my way without incident. I immediately thought of the seaweed I had seen aglow during a nighttime ferryboat crossing from Block Island to Point Judith. Ralph Waldo Emerson had a similar sighting during his visit the Adirondacks in 1858; he described in his journal that his campsite was littered with “decayed millennial trunks, like moonlight flecks, lit with phosphoric crumbs the forest floor.”

Margaret would have none of it.

“You and your friend Mr. Emerson have it wrong,” she said indignantly. “It’s the work of the faeries. The wood-sprites. I’ve seen them. They are most certainly aware you are camping there. They helped you to find your way. You should thank them. They scattered those lights for you,” she said, sounding like a resident of Sleepy Hollow.

**

Margaret was born in 1912 in room 4 of the inn, destined to become a woman of substance.

“I come from a long line of strong women, and I was educated and supported in my career by very strong men,” she told me. “There was never any question that I would do exactly what I wanted to do in life. That’s just how women were always treated in my family.”

She worked with four U.S. presidents; she was interrogated by Sen. Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee in the early 50s, and, before that, traveled with John Reed, author of Ten Days That Shook the World and memorialized in the movie Reds, and with the socialist/author H.G. Wells.

An early role model for Kingman was Margaret Sanger, the founder of the American Birth Control League, now known as Planned Parenthood, and an early advocate for women’s health care. Kingman had been introduced to Sanger by her mother. In July 1931, the two young women sailed to Europe together. Sanger had been invited by the Russian government to visit their birth control clinics and abortion centers, which Kingman says Sanger found “appalling.” Kingman remembers being stopped to have their luggage searched at the Finnish/Russian border. “Sanger was carrying a plaster of Paris model of the female organs, so she could demonstrate how to use a diaphragm,” Kingman recalls. “The authorities examined it with such interest that it delayed our departure and made us miss dinner that night.”

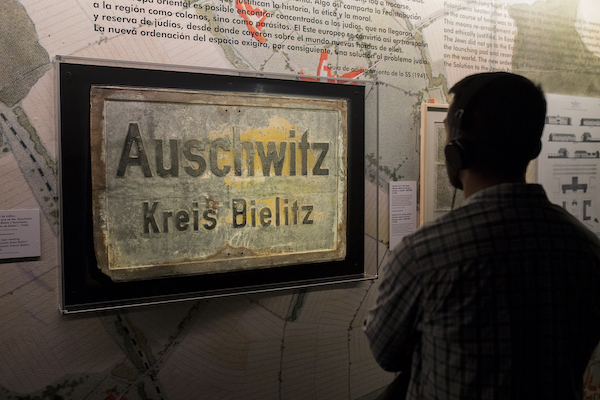

In August of that summer, Kingman witnessed Nazism for the first time. While attending lectures at the University of Warsaw, she saw Jewish students forced to sit in the back of study halls on benches painted bright yellow, the same color as the cloth Stars of David they wore on their clothing, one of the crucial steps the Nazis implemented to dehumanize Jews as criminals of the Reich.

That was the first of her many trips to Europe. She later became involved in the American Youth Hostel movement, which was developing an international network of supervised low-cost lodging for students. She led a group of Smith College students abroad in 1935. After graduating from Radcliffe College in 1934, Kingman studied the relatively new science of photogrammetry –making reliable measurements by the use of aerial photography at the Harvard Institute of Geographic Exploration. After receiving her master’s degree, she taught this science at Smith College.

Although she liked academia, she applied for a position with the government, as did many others during the Depression. Before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, she was asked to join the Coordinator of Information, later known as the Office of Strategic Services (today’s CIA). Essentially an intelligence officer with a cover of “cartographer,” Kingman worked for the combined British and American Chiefs of Staff. She moved back and forth between Europe and the U.S. gathering secret information for the war effort. “In those days, you didn’t tell people what you did or who you worked for,” she said.

After returning from Europe in 1946, she married Lucius Kingman, a lawyer with the Reconstruction Finance Commission and later with the National Labor Board, and bore a son, Louis Jr.

In 1951, Congress summoned Kingman to testify in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee. The committee wanted her to justify her frequent trips abroad in the company of Margaret Sanger, John Reed, and H.G. Wells, all branded as dangerous radicals by Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s red-baiting committee.

“Even though I traveled to Germany and the Soviet Union at different times, I was accused of getting my orders from Russia and then smuggling them into Germany, which was a lot of nonsense,” Kingman recalls. “It was frightening to expect to sit across from Richard Nixon and Roy Cohn, as my immediate supervisor at the OSS and many others I knew had to.”

Nixon at the time was a young right-wing republican congressman from California. He assumed a prominent committee position after his pivotal role in indicting Alger Hiss, the president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, for his participation in communist party affairs in Washington, D.C. Cohn, a young upstart, was a chief counsel for the committee and later president of the American Jewish League Against Communism.

Despite repeated lie detector test clearances and answers of innocence on communist activity, Kingman was denied “Q” clearance from the FBI, the highest clearance allowed.

Even after her ordeal in front of the HUAC, she still managed to perform top secret work with the government — unlike many other blacklisted civil servants who could no longer work in their chosen fields.

When the OSS was dissolved in 1951, she became a cartographic consultant to President Truman’s Water Resource Policy Commission. When the OSS became the CIA, she was again given the chance to perform the top secret work. After 25 years of governmental service, Kingman returned to teaching and the Berkshires and her childhood home. With the help of her students at State University of New York at New Paltz, she made Peirson Place into an inn for summer visitors to Tanglewood.

**

In the late 1980s, Margaret’s health began failing. During a Bob Dylan concert she attended with me and my family at Tanglewood, she was taken by ambulance to Berkshire Medical Center in Pittsfield for treatment for cardiac issues. After she was released, she asked me to arrange a meeting with the Boston Symphony in hopes they might develop Peirson Place as an extension of their Lenox campus for classical music students to live and practice music in return for a promise that she could remain there in perpetuity. The BSO initially favored the idea. They sent representatives to Peirson Place to investigate the property. Then they discovered that she owed a large sum – we’re talking six figures – to the Town of Richmond and to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service in unpaid taxes. In order to take over the property, the matter of these taxes would have to be reconciled. The BSO bowed out.

During one of our last visits, Margaret announced she had made plans to close Peirson Place.

“There is just no way I can manage this place and pay all the taxes they want from me, it’s simply ridiculous. I refuse to be part of it,” she said.

I inquired about the taxes. She bristled. She had earned advanced degrees from Harvard and M.I.T., had taught at Smith and the State University of New York, but she arrogantly maintained that commonplace hurdles we all face as citizens, like paying taxes, were beneath her. “I’ve got too many other tasks that require my attention than to take time out of my busy life to deal with all of that nonsense,” she huffed, and waltzed into the kitchen to fix herself a cup of tea.

The tax collectors from Richmond and the I.R.S. disagreed and forced Margaret’s hand. She paid up by liquidating her assets, including an assortment of antiques, a vintage Volkswagen she could no longer drive, an autographed monograph of the poem “The Congo” by Vachel Lindsay, and a grandfather clock built in the late 1600s in Great Barrington, Mass., by pre-Colonial clockmakers. And she sold a trove of her papers to Harvard’s Schlesinger Library.

Her last letter to me thanked me for my piece that appeared in the Albany newspaper.

“Your newspaper story about me came at a time when my sagging ego needed a lift,” she wrote me. She moved to a Quaker retirement facility in Hanover, New Hampshire, where she died, in 1998, at the age of 86.

**

Endnote: “Dusty” R. Bahlman, a reporter for the Berkshire Eagle, telephoned me years later to ask me to share recollections. His piece was accompanied by a photo of Peirson Place on a snowy morning, boarded up and abandoned. Today a fence surrounds the historic property; the new owners do not welcome visitors.

(Portions of this story first appeared in Times Union, Albany, NY).